In Mandarin Chinese, 干 (Pinyin: gān 🔊) is an adjective meaning “dry”, “dried-up”, “empty”, “exhausted”, “drained” and so on.

Lawrence J. Howell explains in his Etymological Dictionary of Han/Chinese Characters that 干 is a

depiction of a forked stick or thick bar, one functioning as a shield and employed by being thrust or pressed against a combatant in defense. Dry, ebb, draw/drain off and empty (a glass) are borrowed meanings.

Borrowed from where? Well, 干 is a simplified form of the traditional character 乾, which is a phono-semantic compound of phonetic 倝 (gàn 🔊) and semantic 乙. Howell writes that

The relevant bronzeware inscription form is 乙 (rise) + an element combining 日 sun/day and a pennant/banner → the sun likened to a flag that rises high in and adheres to the sky → high and bright sky → dry (← air/water that rises due to heat).

Some compounds of 干 include

- 干 + 冰 = 干冰 (gānbīng): dry ice

- 干 + 季 = 干季 (gānjì): dry season

- 干 + 杯 (bēi) “cup” = 干杯 (gānbēi 🔊): to drink a toast; 干杯! = Cheers!

- 葡萄 (pútáo 🔊) “grape” + 干 = 葡萄干 (pútáogān 🔊): raisin

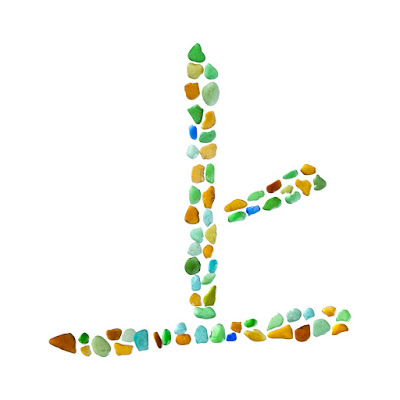

Incidentally, the symbols above were created using some yummy 葡萄干.

More photos related to raisins and other dried stuff @ Shutterstock.