The lemniscate or ∞ is a mathematical symbol for infinity.

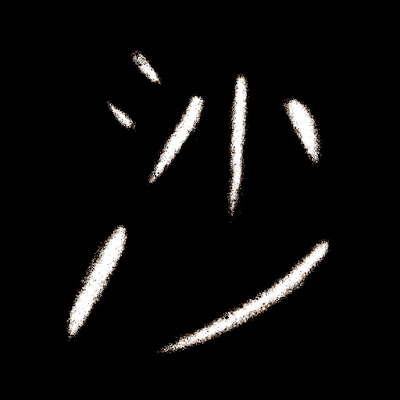

The Englishman John Wallis (1616—1703) is credited with introducing the infinity symbol to mathematical literature. One hypothesis is that ∞ is a variant form of ↀ, a Roman numeral (later replaced by Ⅿ) for 1000, which was figuratively used to represent very large numbers, just like Chinese 万 (ten thousand) may also mean “countless”. Most uses of ∞ outside of math, such as in mysticism, or as related to gender identity/sexuality, still have something to do with the infinite. For example, the infinity heart, a combination of ∞ with ♥, is a symbol of polyamory. For me, the figure above looks like the tracks of “either Two Woozles and one, as it might be, Wizzle, or Two, as it might be, Wizzles and one, if so it is, Woozle”.

More photos related to infinity, numbers and sea glass @ Shutterstock.